Soundtrack for this article: Summer by Joe Hisaishi, 1999.

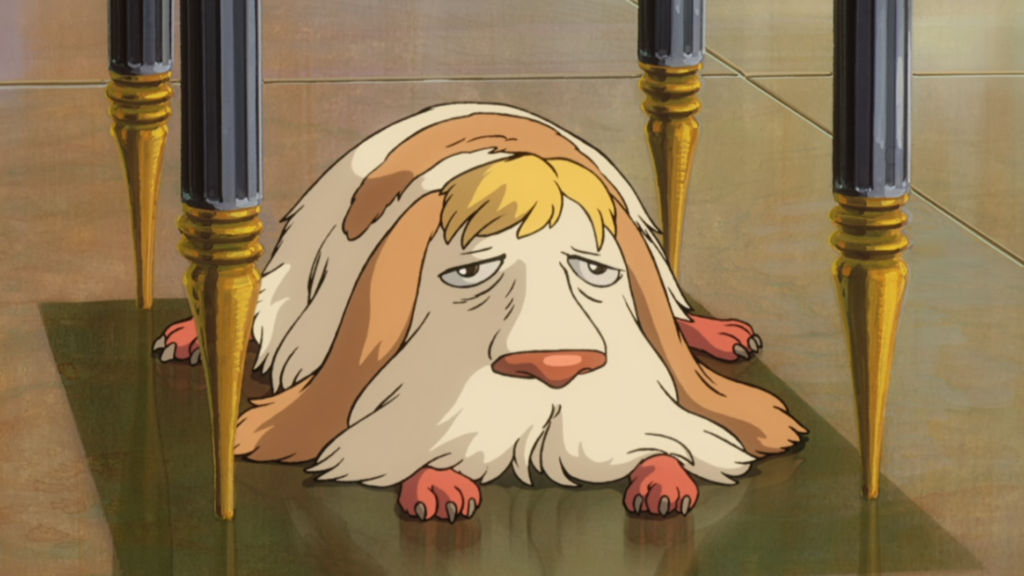

Heen is a lazy, shaggy, floppy-eared dog, who only communicates through wheezing and gasping, jumping and scraping.1

Dogsonification has been an effective narrative device used in major Studio Ghibli titles Howl’s Moving Castle, Kiki’s Delivery Service, and Princess Mononoke (my personal favourite).

In Kiki’s Delivery Service we meet Jeff, a 12-year-old St Bernard who shares a wonderful scene with Kiki’s cat Jiji. Jeff is a real dog in this film, and actually enables the toyification of Jiji, so is not an example of dogsonification except in how he makes the film more lovable.

Heen, from Howl’s Moving Castle, is a little more complex. We are introduced to him early in the film in an important scene where old-Sophie must climb a long and difficult stair. Sophie believes that Heen is the magical dogsonification (actually transdogrification) of the wizard Howl Jenkins Pendragon. Thus it seems incredibly unfair when Heen needs the frail Sophie to haul him up the stairs, as his tiny legs cannot make the steps. We later see that Heen is perfectly capable of flying using his long hound ears, and this was really just him being lazy. By the end of the film we are 95% sure that Heen is just an ordinary animal, with a little dash of magic.

It is in Princess Mononoke where dogsonification is featured to drive the central theme of balance between humans and nature. The adopted daughter of the Wolf-God Moro is San (aka the Princess Mononoke). San was raised from an infant by Moro and treats her as a mother, with Moro’s wolf children as her siblings. San’s emotional arch through the film is her journey to reconciling her humanity, sparked through falling in love with the cursed prince Ashitaka. It is really through her heart where the theme of balance plays out. In the end she cannot forgive humans for what they have done to the forest and forest beings, and remains of that realm. You can see this theme extended through the 2012 film Wolf Children – directed by Mamoru Hosoda and distributed by Toho, not Ghibli – where instead of playing out in San’s heart, the theme of human and nature is explored through the choices of two siblings.

Some maintain that the 1994 Ghibli classic Pom Poko is the best example of dogsonification in the Ghibli cannon, but I don’t think so. While the film’s lovable Tanuki (Nyctereutes procyonoides viverrinus) are relatives of dogs, it is actually through personification that we are encouraged to care for them. We see the Tanuki as good-hearted villagers living simple lives but to the films land-developing antagonists they are dangerous wild animals.

Why has dogsonification become such a reliable device with which to discuss the balance of human and nature? Is it because domesticated dogs represent a halfway point between a heart that is wild and civilised?

I think it is done, as the best living human might say, for love. If we love wild nature, then we will try to find a balance. After all, what is a more lovable ambassador of nature than the family dog?

But for better or worse we are not like the family dog.

Fido has been selectively bred for peace and civility, but the hearts of humans are still as raging and wild as they were a hundred thousand years ago. Perhaps we are still wild things, cloaked in the thin glamour afforded us by civilisation? Perhaps we need to learn a love of wild things because we are wild things too?

And maybe we love dogs so much because they can still see how wild and fucked-up we really are… How else would you explain the way they roll their eyes at us with such patient concern?

12 November 2024, looking at Heen.